The Government’s Plan for Growth

Alongside the March 2021 Budget, the Government published Build Back Better: our plan for growth – reframing and repackaging the Industrial Strategy of 2017, with innovation, skills and infrastructure at the heart of this “new framework [to] build back better.”

The Plan refreshes its ambitions for Global Britain™ as a Science Superpower™ leading the Green Industrial Revolution™, transforming our skills base to boost growth and productivity across the whole of the UK.

Of course, the above might sound familiar if you’ve been following Government policy for the past few years, so what are some of the key takeaways from this latest statement of government industrial policy?

Levelling up vs growth

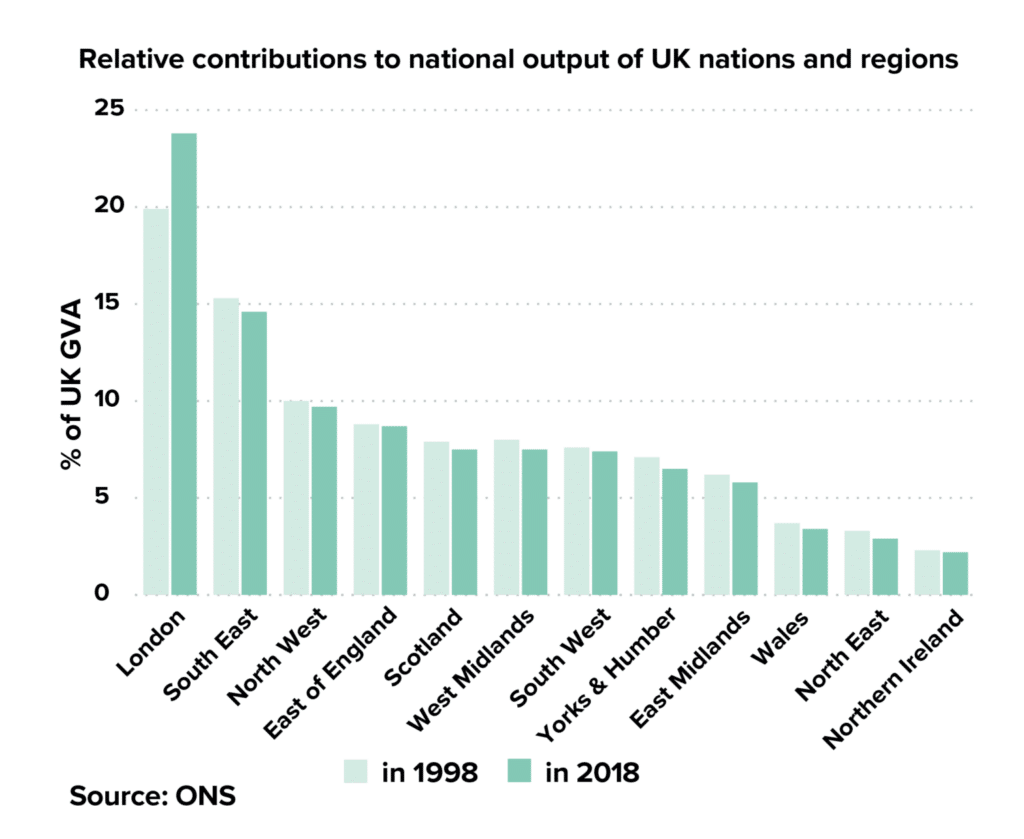

In 2017 the Industrial Strategy acknowledged regional inequalities as one of a number of issues to be addressed, but the Plan for Growth puts growth outside the south of England as a ‘primary objective’ of the Government, with every UK region having a least one internationally competitive city.

In his foreword the Prime Minister doesn’t hold back: “Talent and resources have been sucked to the south” and the rest of the country has suffered. The election earthquake of 2019 wrecked Labour’s Red Wall, and government policy is now, more than ever, geared towards realising the economic potential (and keeping the votes) of those areas outside the south. Politically, it’s crucial that headline projects are seen to be being delivered before the next election to help retain red wall seats – expect lots of ribbon cutting. (That 40 of 45 areas covered new £1 billion Towns Fund map closely to Conservative constituencies has been noticed.)

As such, progress with levelling-up will dictate the overall success of the Plan for Growth. Failure will mean that research priorities, investment are compromised and diluted by clumsy Government demands to deliver results in particular areas. But success here would deliver powerful returns as a greater proportion of the country comes closer to delivering the productivity and dynamism seen in London and the south-east.

From ARPA to ARIA

Place your bets please. One of the more high-profile parts of the Government’s Plan is the forthcoming Advanced Research and Invention Agency which will have £800 million to fund high-risk, high-reward research. Heavily pushed by Dominic Cummings, the intention is to embed a new agency with the patience and independence to embark upon research projects with longer-term, but potentially much more lucrative payoffs.

Sceptics note that £800 million when it comes to research won’t go far – Google spent £27 billion on R&D in 2020. The House of Commons’ Science and Technology Committee recommended the new agency should focus on “two strategically important missions” to avoid being stretched too thinly, and that Government should clarify its purpose and where it reports into Whitehall.

Earlier this week Government published legislation for the creation of the ARIA, which included a 10-year grace period before any potential dissolution of the agency can be triggered. This attempt at preserving the agency from political interference shows the pressure the new body will be under: high-risk doesn’t necessarily mean there will be high reward. Of course, there is nothing to stop a future Government re-legislating independence and lifespan of ARIA, ten years is a very long-time in politics (a decade ago Vince Cable was Business Secretary, Britain was solidly in the EU and the already redundant Fixed Term Parliament Act was passed).

Regulatory freedom outside the EU

One of the oft-touted benefits of Brexit was the opportunity for the UK to remove the heavy hand of Brussels, and put in place the most pro-growth, pro-innovation regulatory regimes in the world. Last month the Prime Minister asked three of his colleagues to lead the Taskforce on Innovation, Growth and Regulatory Reform (‘TIGGRs’ are wonderful things) to identify a list of reforms which could be implemented quickly to spur growth.

Government has established the Regulatory Horizons Council to advise on regulatory recommendations for emerging technologies, and the Better Regulation Committee has been given increased profile and tasked with being ambitious on the reform agenda.

There are some exciting ideas within this which have been floating around for a while. A variety of new technologies – life sciences, drones, automotive – need supportive regulatory environments to drive research and development. In addition, the great strides forward in data and analytics make it conceivable to implement real-time, responsive, and data-driven regulatory adjustments. This capability is already well provided by leading analytics companies such SAS providing data driven, real time systems to establish a feedback loop of continuous improvement. By rethinking traditional methods of governance and assurance, not just the regulations themselves, Government has an opportunity to tame complexity, bake-in compliance and unlock value in a fast-changing, high performance world

Time will tell whether the UK is about to enter a new, exciting phase as some sort of global regulatory laboratory for emerging technologies or come up hard against the regulatory demands of the other economic superpower as well as the concerns of British public.

The long road to 2.4%

Perhaps the best recognised of the Government R&D goals, set in IR2017 was for the UK to increase its total R&D expenditure to 2.4% of GDP by 2027, and 3% in the longer term. (UK R&D has stubbornly hovered around 1.7% of GDP since the early 1980s).

There are now just six years to achieve this ambition, and despite an increase in public investment (BEIS R&D saw a funding increase of 19% in the Budget last year) achieving 2.4% will require a substantial increase from private investors – and these are not good economic times.

There is also a tension in Government between attracting foreign investment and ensuring UK national security interests are not harmed. At the same time as Government has set up its new Office for Investment, it is advancing legislation which will grant Ministers significant powers in the National Security and Investment Bill to intervene where it feels UK interests are at risk.

As such, expectation will be high when Government’s Innovation Strategy for High Growth Sectors and Technologies is published later this year.

We do know the UK Government will commit £375 million to build on the Future Fund, with Future Fund: Breakthrough which will direct co-investment product to support the scale up of the most innovative, R&D-intensive businesses. The British Business Bank will take equity in larger funding rounds led by private investors to ensure these companies can access the capital they need to grow and deliver prosperity to communities across the UK.

The Government needs to maximise the return on the great science emerging from the Public Sector Research Establishments, and work of the United Kingdom Innovation and Science Seed Fund (UKI2S) shows how it should be done – supporting these companies with investment and advice at the earliest stage of the commercialisation pipeline.

Outlook

The Plan for Growth is a relaunched prospectus of Government industrial priorities forged back in the political battles and election of 2019. Since delayed and overshadowed by the pandemic of the past twelve months, it represents a significant evolution of the original Industrial Strategy, setting the highest ambitions and placing great faith in the ability of public policy to achieve them (2.4%, levelling-up, a regulatory revolution to name a few)

The underlying philosophy of the Plan was originally generated from a shifting map of swing-constituencies and as a response to Brexit realities/politics, but the addition of the global pandemic further reinforces the Prime Minister’s argument for bold and risky approaches. For now, Government is at pains to emphasise its commitment to the Plan over the long-term. The question is whether Government will be able to sustain this approach in the years ahead, or whether political (mis)fortunes and election planning will warp and bend the Plan for Growth out of shape.

If you would like to speak to the April Six Public Affairs teams about your political and policy engagement requirements please contact vernon.hunte@aprilsix.com